Calcium might just be the most well-known mineral thanks to things like the dairy-industry-sponsored “Got Milk?” campaign from years ago. It’s true that calcium is really important for the mineralization of bones and teeth, strengthening them and maintaining that strength as we age. But, did you know that calcium is also important for communication between cells?

As I already mentioned, calcium is the major structural component of bones and teeth (see also Why Don’t I Need to Worry About Calcium?). Our bones are constantly remodeled throughout our lives; a hormone called parathyroid hormone (PTH) closely regulates the amount of calcium in our blood, sometimes by “borrowing” calcium from bones that will hopefully be deposited again if there is enough calcium intake. Calcium also helps to regulate the constriction/relaxation of blood vessels, nerve impulses, muscle contraction, and secretion of hormones like insulin. This is all controlled by differences in electrochemical signaling inside and outside of cells, as well as the flow through cellular membranes that can change these gradients (aren’t bodies amazing?!). So, the concentration of calcium in certain tissues is extremely tightly regulated, because it impacts hugely important functions like communication in the nervous system or contractility of our heart.

What happens when we don’t get enough calcium? Well, like I mentioned, our bodies tightly regulate the amount of calcium in our blood, so our bodies will sacrifice bone mineralization to make sure that there is enough circulating calcium. Over time, this can cause osteoporosis (I know you saw that one coming!). Getting enough calcium is also associated with decreased risk for kidney stones and pregnancy-induced high blood pressure disorders (such as gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia). Plus, there is evidence that adequate intake of calcium reduces our risk of colorectal cancer!

Scientists have also studied whether supplementation with calcium can specifically treat diseases. There is some evidence that low calcium is associated with high body weight (i.e., obesity), and some clinical trials have demonstrated that supplementation with 1200mg/day of calcium can aid in weight loss. This suggests that calcium plays a role in weight regulation, perhaps by increasing muscle efficiency, regulating appetite, or generally improving hormone signaling. Interestingly, calcium supplementation has been shown to improve the symptoms of PMS – this may be due to improved nervous system function (better mood) and/or adequate muscular signaling (reduced cramping). Doctors are also using calcium to treat hypertension; this makes sense considering its role in the contraction and relaxing of blood vessels.

Because our blood levels of calcium are tightly controlled by PTH, most cases of calcium deficiency in the blood are related to abnormal PTH function. Testing whether there has been adequate intake of calcium over time is best done with a bone scan, because this is a reliable measure of where calcium is stored. The RDA for calcium, like most nutrients, changes as we age, with the highest requirement being during adolescence (1300mg/day). The RDA for adults 19 to 50 years old is 1000mg/day, and data suggests that upwards of 40% of adults are not getting enough calcium in their diet (and I suspect it would be much less if we didn’t count dairy intake, which accounts for 75% of Americans’ calcium intake! Seriously.).

Because our blood levels of calcium are tightly controlled by PTH, most cases of calcium deficiency in the blood are related to abnormal PTH function. Testing whether there has been adequate intake of calcium over time is best done with a bone scan, because this is a reliable measure of where calcium is stored. The RDA for calcium, like most nutrients, changes as we age, with the highest requirement being during adolescence (1300mg/day). The RDA for adults 19 to 50 years old is 1000mg/day, and data suggests that upwards of 40% of adults are not getting enough calcium in their diet (and I suspect it would be much less if we didn’t count dairy intake, which accounts for 75% of Americans’ calcium intake! Seriously.).

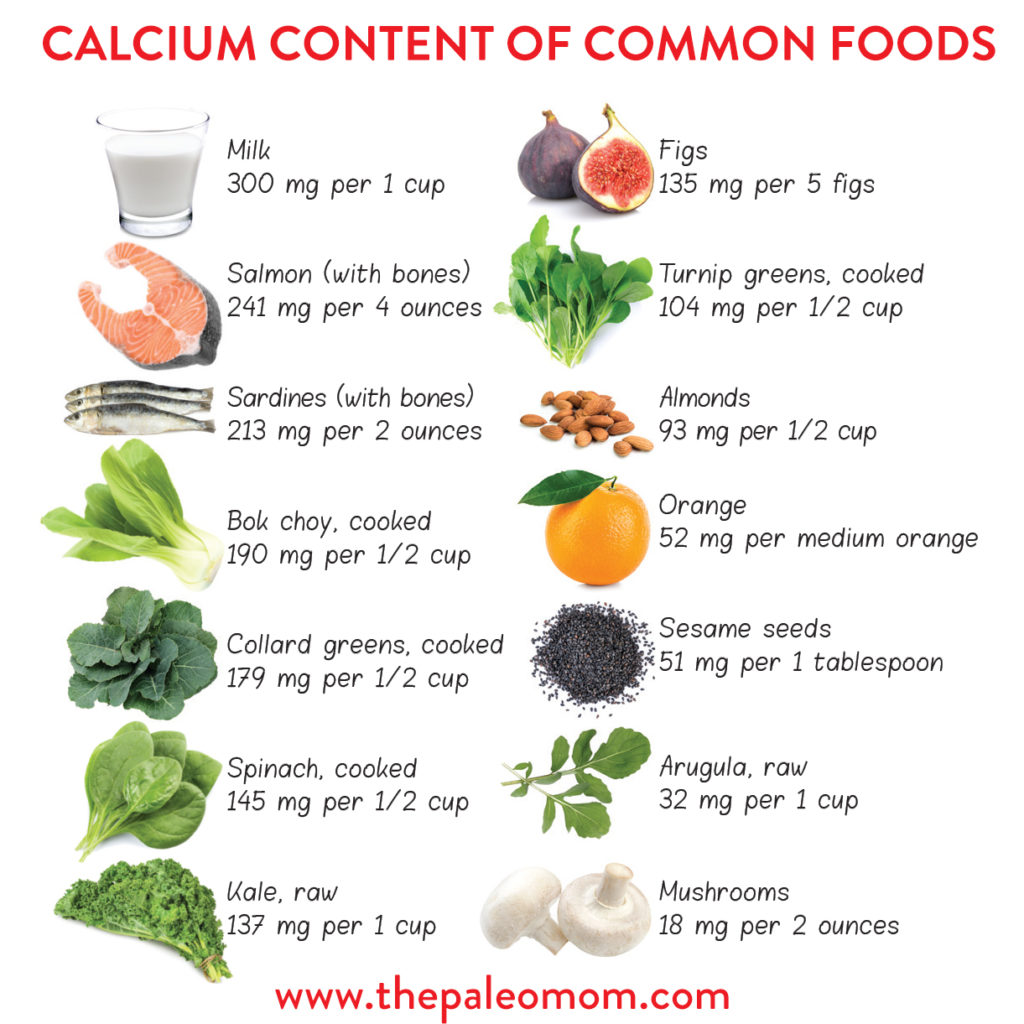

Working within the Paleo template, what are the most calcium-rich foods? The very best is sardines, which have 351mg of calcium per can. Another great source of calcium is the Brassica family of foods: broccoli, kale, bok choy, cabbage, mustard, etc. One cup of cooked kale as 101mg of calcium! These plant sources of calcium are specifically amazing, because their calcium content is as bioavailable as animal sources (whereas the oxalate content in some other plant foods is a strong inhibitor of calcium absorption). Other good sources include dark green vegetables, whole sesame seeds, dairy products, and squash.

Citations

Weaver CM. Calcium. In: Erdman JJ, Macdonald I, Zeisel S, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 10th ed: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2012:434-446.

Carbone LD, Barrow KD, Bush AJ, et al. Effects of a low sodium diet on bone metabolism. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23(6):506-513.

Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, D.C.; 2011.

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381.

Boron

Boron